Home - Index - News - Carl Bildt 1992 - EMU - Cataclysm - Dollar

Stagflation: a term coined by economists in the 1970s to describe the previously unprecedented combination of slow economic growth and rising prices.

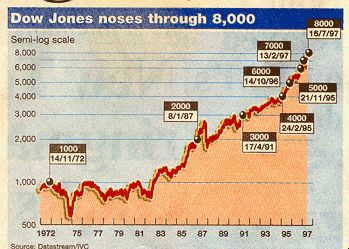

The last three recessions, likely to be the only frame of reference for most people working in financial markets, might prompt more of an inflationary shrug

For the first time in a decade, the biggest risks are now stagflationary (slower growth and higher inflation).

These risks include the negative supply shock that could come from a trade war; higher oil prices,

owing to politically motivated supply constraints; and inflationary domestic policies in the US.

Nouriel Roubini Project Syndicate 18 July 2018

We must heed warnings from the 1970s bear market

The first quarter of 1975 saw the end of the most savage bear market for stocks since the 1930s.

John Plender FT 25 April 2018

Recognising the conditions that change the longer trend of returns is more important than trying to time the peak

New perils lurk, not least among the high-frequency trading fraternity that provides only fairweather liquidity to the markets. A growing proportion of money is managed pro-cyclically and in ways that are insensitive to price or value.

More broadly, levels of debt are higher than before the great financial crisis and the leverage implicit in derivative instruments is on a scale that would have seemed unimaginable back in 1975.

Markets Better Prepare for Stagflation

By all metrics, prices are heating up. But the same can't be said for economic activity.

Danielle DiMartino Booth Bloomberg 24 april 2018

Rising prices and collapsing confidence could portend that both inflation and slowing growth are looming, a sure recipe for stagflation.

All this would undermine elevated asset markets and might trigger worries over debt sustainability.

In a still fragile world economy, the results might be ugly. One might even see a return to the stagflation of the 1970s, with far lower inflation, but also far higher indebtedness.

The starting point is a puzzle: why is inflation so low when the rate of unemployment is already a little below the level the Fed (and most economists) consider to be “full employment”

(the rate at which inflation should start to accelerate upwards).

Martin Wolf FT 10 October 2017

“The real problem is that when the bond-market bubble collapses, long-term interest rates will rise,” Greenspan said.

“We are moving into a different phase of the economy -- to a stagflation not seen since the 1970s.

That is not good for asset prices.”

Bloomberg 1 August 2017

An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy

Book by Marc Levinson, formerly finance and economics editor of The Economist

Stagnant wages. Feeble growth figures. An angry, disillusioned public.

The early 1970s witnessed the arrival of the problems that define the twenty-first century.

Why we’re reliving the 1970s

Simon Kuper, FT 15 April 2016

The west, it’s said, is going back to the 1930s. Then as now, we have urban violence, economic stagnation, rising populists and a menacing Russia. Isis is auditioning for the role of Nazi Germany.

The 1930s analogy could still prove correct. But, so far at least, there’s a more plausible comparison. Our current era is more similar to the 1970s than the 1930s.

Like all historical parallels, this one is imperfect: the 1970s had inflation, we have inequality. But the echoes are loud. Terrorism was arguably even bloodier then.

Then as now, western governments looked feckless. They, too, suffered from elite rot: in 1974 Richard Nixon resigned over Watergate, three months after West Germany’s chancellor Willy Brandt had quit when his close aide Günter Guillaume was exposed as an East German spy.

Rather than inflation creating stagnation, we have deflation dragging the economy to stagnation.

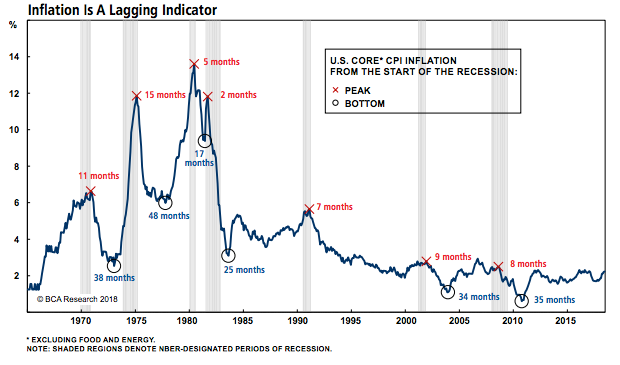

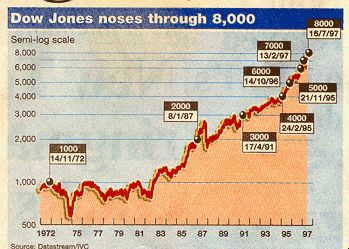

Back then, a 37% and 49% decline in equity prices wasn’t called a crash but instead a bear market.

Don't expect a crash — expect a continued bleed.

L.A. Little, MarketWatch Feb 21, 2016

The analytical underpinnings of the current phase of risk taking in financial markets are far from robust.

Less pleasant scenario – that of stagflation and greater financial instability.

Mohamed El-Erian, FT 14 July 2014

This configuration of more balanced risk is not yet reflected in asset prices and the levels of implied and realised volatility.

Mohamed El-Erian is chief economic adviser to Allianz, chair of President Obama’s Global Development Council and author of “When Markets Collide”

Stagflation

Don’t trust anyone under 61

Dagens 30-åriga börsmäklare föddes år 1984.

Man kan inte begära att dom skall ha någon egen minnesbild av vad som hände 30 år tidigare,

mellan den 11 januari 1973 och den 6 december 1974,

då Dow Jones förlorade över 45% av sitt värde.

Rolf Englund blog 2014-07-13

Kenneth Rogoff, former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund and now a professor at Harvard University,

Given the low growth, he says, inflation above central banks’ targets could be helpful:

“A bit of inflation is by far the lesser evil compared with even lower growth.

Five per cent inflation for 2 to 3 years is not the end of the world. There are even some benefits.”

Financial Times 13 may 2011

These benefits relate to the levels of debt in the west, a problem he calls “utterly profound”.

Inflation may help with “deleveraging”, or cutting debt, as it reduces the sum to be paid back.

Mr Rogoff contrasts today’s situation with four decades ago:

Realräntor - Real Interest Rates

Stagflation Versus Hyperinflation

Textbook economics makes a real distinction between the kind of

inflation that bedeviled the 1970s and 1923-type hyperinflation.

Paul Krugman 18/3, 2010

The Fed's rate dilemma

Interest rates likely on hold for a while as worries about economic weakness and inflation leave central bank with few good options.

CNNMoney.com August 1, 2008

"This is the third time in 100 years that support for taken-for-granted economic ideas has crumbled.

The Great Depression discredited the radical laissez-faire doctrines of the Coolidge era.

Stagflation in the 1970s and early '80s undermined New Deal ideas and called forth a rebirth of radical free-market notions.

What's becoming the Panic of 2008 will mean an end to the latest Capital Rules era."

Warren Buffett says he's concerned about ``stagflation,''

Bloomberg June 25 2008

``We're right in the middle of it right now,'' said Buffett, chairman of Omaha, Nebraska-based Berkshire Hathaway Inc., in an interview on Bloomberg Television today. ``I think the `flation' part will heat up and I think the `stag' part will get worse.''

Buffett, the world's richest person, runs a company with a $72 billion stock portfolio and businesses ranging from candy to corporate jet leasing and insurance. He's said the U.S. housing slump has been a drag on Berkshire's earnings, adding today he's unsure when the economy will recover.

``It's not going to be tomorrow, it's not going to be next month, and may not even be next year,'' said Buffett, 77.

21st-century stagflation:

a toxic brew of soaring inflation and slumping growth.

Edmund Conway, Daily Telegraph 11/6 2008

The return of stagflation - or globeflation, or whatever peculiar name the wise men will give it - is an international phenomenon, with higher prices generated by China's rising economy and the fear that we may be running out of oil/metals/food/water.

Rejält höjda förväntningar om den framtida inflationen spär på rädslan för en elakartad pris-lönespiral à la 1970-tal.

DN-ledare 28/5 2008

The Bank of England governor has raised the spectre of stagflation in Britain, warning that we are facing "rising inflation and falling economic growth".

families are facing the "longest period of financial turmoil that most of us can remember"

Daily Telegraph 10/6 2008

Inflation and the lessons of the 1970s

Wolfgang Münchau, FT May 25 2008

Inflation is rising and it seems the world’s central banks have critically misjudged the situation. Until a few months ago, most commentators worried about a repeat of the Great Depression. But the 1930s have virtually no relevance to our situation – except that some paranoid economists remain obsessed with this period. The only historical period that bears any resemblance to what is happening today is the 1970s.

Then, and now, an oil price shock turned into a rise in the general price level. Both then and today, central banks largely accommodated this price rise, which was a mistake then and is a mistake now.

Jean-Claude Trichet, president of the European Central Bank, this week gave warning about the mistakes of the 1970s, when inflation was let loose at huge cost to growth.

the average world real interest rate is negative.

The Economist print May 22nd 2008

Central bankers' mistake then was to hold monetary policy too loose, so that higher oil prices quickly fed into other prices. So it is worrying that global monetary policy is now at its loosest since the 1970s:

the average world real interest rateis negative.

As Asian economies and Middle East oil exporters ran large current-account surpluses, they piled up foreign reserves (mostly in American Treasury securities) in order to prevent their currencies from rising.

This pushed down bond yields.

At the same time, cheap imports from China and elsewhere helped central banks in rich economies hold down inflation while keeping short-term interest rates lower than in the past.

Cheap money fuelled America's bubble.

Even if the Fed's interest rate suits the American economy, global interest rates are too low.

Why inflation is not the big problem

Soaring food and energy costs are painful, but falling home prices could mean even bigger worries.

CNN May 9, 2008

Even if financial firms avoid another crisis along the lines of the near-meltdowns earlier this year of Bear Stearns and Countrywide (CFC, Fortune 500), some economists say problems in the financial sector are only beginning to be felt on Main Street.

"The real economy hasn't yet taken the hit," says Northern Trust economist Asha Bangalore.

Who gives a damn about inflation?

Wolfgang Münchau blog 31.01.2008

IMF's first deputy managing director, John Lipsky, 61, a former JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief economis:

Inflation is emerging as a threat to economic stability after years of ``quiescence,''

A return to 1970s-style high inflation and rising price expectations ``cannot be discarded out of hand

May 8 2008 (Bloomberg)

After an exceptionally benign period of virtually universal advances in economic performance—that helped to carry many financial markets into uncharted territory—investors have suddenly become more cautious.

This search for new market ranges may take some time, and it is likely to involve additional volatility.

However, the degree of recent market turbulence should not be exaggerated.

The fundamental underpinnings of the current global expansion appear to be reasonably solid.

John Lipsky, July 31, 2007

Pessimistic pundits emphasize the dangers lurking in unsustainable trade and payment imbalances, excessive liquidity, savings shortfalls, dollar overhangs and global reflation

Money also talks, however, and its message has failed to echo the pundits' pessimism.

JOHN LIPSKY and JAMES E. GLASSMAN Wall Street Journal February 16, 2005

US Consumer prices rose 0.8% in November from October

Inflation in the eurozone also surged - consumer prices rose 3.1% Y/Y

2008-05-07

Mr. Volcker noted that when "concerns about recession are rife," the central bank will be tempted to "subordinate the fundamental need to maintain a reliable currency" to the impulse to shore up a flagging economy.

The danger is that you lose both battles, as the U.S. did in the 1970s, and wind up with stagflation.

Wall Street Journal 9/4 2008

Mr. Volcker also argued Tuesday that the Fed's strenuous efforts on behalf of the housing market risked looking "biased to favor particular institutions or politically sensitive constituencies," in this case the housing industry. He did not argue that no government intervention was warranted – the crisis was, he said, "too threatening" for the government to stand aside.

Mr. Volcker argued against a further extension of this /Bear Stearns/ implicit Fed guarantee to hedge funds or private-equity groups, whose failure pose little risk to the system as a whole. Right about now wouldn't be the worst time for such a hedge-fund blowup, if only to show that the Fed will let it fail.

Soaring commodity prices, rising headline inflation and weakening economic growth:

for those whose memories stretch back to the 1970s, this combination brings painful memories. It reminds them of the mistakes made by the central banks that accommodated the upsurge in inflationary expectations rather than contained them. Inflation was finally brought back under control in the early 1980s. But the costs of letting it escape were huge.

Could we be making the same mistakes again?

Martin Wolf, FT March 4 2008

As Richard Fisher, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas noted in a speech delivered in London on Tuesday: “Since the January federal open market committee meeting, longer-term rates, including those on fixed mortgages, have risen rather than followed the federal fund rates downward.” In such circumstances, aggressive monetary policy may have weak, even perverse, effects on the real economy.

In the US today, inflation expectations are on a knife edge. As I noted last week, the expectations shown in the relation between inflation-indexed treasuries (TIPS) and conventional bonds appear to be quite well contained. But the Cleveland Fed offers a “liquidity adjusted series”, which allows for the desire to hold more liquid assets in a period of financial stress. On this measure, expected inflation is soaring (see chart). The Fed’s position is now uncomfortable. The assumption that it can cut rates without fear of the consequences is wrong.

Personal spending rose 0.4% last month, but inflation rose 0.4%,

Eonomists say there is a danger of "stagflation".

However, Ben Bernanke told US lawmakers that he did not expect a period of stagflation.

BBC 29/2 2008

CNN

Worries about 1970s-style stagflation have moved to the forefront to rival recession fears.

CNN 21/2 2008

Recession has been getting so much attention lately that it's been easy to forget about the threats posed to the U.S. economy by inflation.

I invented a new index yesterday.

To be known as Stevenson's Stagflation index (SSI),

it measures the number of articles in which my press cuttings database finds a mention of that unholy combination

Tom Stevenson, Daily Telegraph, February 12, 2008

The number of "stagflation" hits so far this year is 719. In the past six weeks the word has been used more than in all of 2003. At the current rate, my target for the year-end is about 6,000, a 200pc rise in a year.

The worst of all possible worlds is when inflation rears its ugly head even as growth slows. Stagflation holds a special place in the dark corners of economists' minds because it renders a central banker's monetary armoury powerless to fight a uniquely debilitating condition. He can't stimulate growth with lower interest rates because prices will take off and he can't bash inflation with higher rates because it will tip the economy into recession.

US annual inflation, 4.1 per cent, rising at fastest since 1990

FT January 16 2008

Prices for US consumers rose at a faster than expected pace in December, pushing inflation to its highest yearly increase since 1990. But inflation concerns are likely to take a back seat as the Fed seeks to avert a recession, economists said.

The rise in inflation over the whole of 2007 was 4.1 per cent, the highest rise since a 6.1 per cent jump 17 years ago. This was still less than in November when the year on year price rise was 4.3 per cent, lifted by soaring energy prices.

The higher-than-expected figure raises fears of stagflation, as slowing growth in the US economy is complemented by higher rates of inflation.

US inflation jumped to an annual rate of 4.3 per cent in November

highlighted the risk the economy will face at least a brief period of “stagflation”

FT December 14 2007

What should they do if the economy is faced with both increasing inflation and severe growth slowdown?

This is the dilemma of stagflation.

Samuel Brittan, FT December 6 2007

There is not all that much difficulty in steering a modern economy when it is faced with one main danger. If that is inflation, the need is clearly to rein back on the growth of demand.

Should the main danger be recession or a severe slowdown it will need to apply a stimulus, for instance by lowering the policy-determined short-term interest rate.

A point may indeed be reached where monetary policy needs to be supplemented by fiscal policy,

which is a posh way of describing lower taxes or higher public spending, in principle temporary.

Far from the stagflation dilemma being a new problem, it is one that has recurred at least once every decade since the 1970s.

But we are still far from a solution.

A tentative answer to the dilemma was suggested by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in the 1970s and 1980s, known by the label of “non-accommodation”.

The first job now is to convince people that monetary relaxations this winter in spite of rising inflation represent a tactical retreat and not the start of a headlong rout.

The US economy is leading the way, having already entered a stagflationary phase.

Such an environment is poisonous for financial assets.

Tim Bond, head of asset allocation for Barclays Capital 6/12 2007

Since 1929, the average real return from US equities, bonds and bills has been markedly negative during years of below trend growth and above trend inflation. Equities, by way of example, average a negative 1.9 per cent real return during such years.

Neither the US equity market nor the corporate bond market appear aware that a profit margin contraction is under way.

During such periods, investors are best served keeping most of their allocations in cash and inflation-linked securities.

How do You Spell Stagflation?

John Mauldin 16/11 2007

Quoting Williams: "Up until the Boskin/Greenspan agendum surfaced, the CPI was measured using the costs of a fixed basket of goods, a fairly simple and straightforward concept. The identical basket of goods would be priced at prevailing market costs for each period, and the period-to-period change in the cost of that market basket represented the rate of inflation in terms of maintaining a constant standard of living.

The Fed faces a problem something like that. They are living in a two dimensional world, working with two dimensional tools (they can cut rates or raise them) but the problems they face are multi-dimensional.

If they cut rates, the dollar will fall and import prices rise, and it will also likely have negative effects on food and energy prices. If they do not cut rates, the markets will simply throw up as it will interpret that as a Fed which is not concerned about a slowing economy.

Not cutting rates risks an economy that could easily slip into recession due to a growing risk of a credit crisis turning into a credit crunch. Usually, that means that inflation will fall. Usually, but not always.

It has all the hallmarks of stagflation.

The economy is heading for a major slowdown , perhaps the sharpest one in a decade and a half; the housing market is already starting to turn; financial markets still look extremely shaky, with the worst of the bad news from the big investment banks maybe still to come.

Daily Telegraph 2007-11-14

Compelling reasons for the Bank of England to consider cutting interest rates from their current level of 5.75pc, by far the highest in the G7.

But that old bogeyman, inflation , won't let them get away with it. News that the Consumer Price Index rose to 2.1pc in October is the latest evidence that the Monetary Policy Committee is facing a similar beast to the stagflation of the 1970s , falling growth rates combined with sticky and high inflation.

Unless there is a steep fall in oil and food prices soon, there is a strong possibility of stagflation in the US next year.

In such a situation, there are no easy policy choices.

Wolfgang Munchau, FT November 11 2007

With skinny trousers and Mary Quant dresses, fashionable Americans are taking their cues from the 1960s this spring.

For financial markets and central bankers the retro theme comes from a different, less pleasant, decade.

With growth slow yet inflation stubborn, America is facing a weak echo of that 1970s scourge—stagflation.

The Economist print edition May 3rd 2007

Financial markets reckon the Fed will eventually fear recession more than inflation. The price of Fed and eurodollar futures suggests that the central bankers are very likely to cut rates by at least a quarter point in the second half of the year, with more loosening likely early in 2008.

If, as I believe, the US economy has already reached the stagflation phase

rising interest rates come at a very inopportune time for the economy and also for asset markets.

Dr. Marc Faber June 09 - 2007

The only way the US dollar can strengthen is to have relatively tight money in the US, which then has negative implications for asset markets.

Bernanke’s Sophie's Choice:

"The housing market or stock market Mr. Bernanke.

You may only be able to try and save one..."

Mild stagflation, predicted as the ultimate outcome of radical Fed easing in this column five years ago, is now here.

So, how does the market react to the bad news? By going higher, naturally.

It has now been up 19 of the last 21 trading days. Amazing.

John Mauldin, 27/4 2007

Jeremy Grantham is chairman of Grantham Mayo Van Otterloo, which manages around $150 billion. He is famous for his value orientation and research.

I quoted this bit from Barrons about four years ago:

"My colleague Ben Inker has looked at every bubble for which we have data. His research goes back years and years and includes stocks, bonds, commodities and currencies. We found 28 bubbles. We define a bubble as a 40-year event in which statistics went well beyond the norm, a two-standard-deviation event.

Every one of the 28 went back to trend, no exceptions, no new eras, not a single one that we can find in history."

Everything is in bubble territory, he says. Everything. "From Indian antiquities to modern Chinese art," he wrote in a letter to clients this week following a six-week world tour, "from land in Panama to Mayfair; from forestry, infrastructure and the junkiest bonds to mundane blue chips; it's bubble time!"

"The mechanism is surprisingly simple," he wrote. "Perfect conditions create very strong 'animal spirits,' reflected statistically in a low risk premium. Widely available cheap credit offers investors the opportunity to act on their optimism."

And it becomes self-sustaining. "The more leverage you take, the better you do; the better you do, the more leverage you take. A critical part of a bubble is the reinforcement you get for your very optimistic view from those around you."

About Jeremy Grantham: All the World's a Bubble

Jeremy Grantham: All the World's a Bubble

Second, money supply does matter. We are seeing the broad money supply indicators (M-2 and M-3) rise not only in the US but all over the world. This is not a central bank pumping function but a market-driven phenomenon, as leverage is increasing the capital deployed in today's markets. The central banks of the world have largely lost the ability to control the money supply, other than by the narrowest of measures, which are increasingly less meaningful. We are not seeing the rapid increase in money supply show up in inflation or loss of buying power but rather as inflation in asset prices of every kind, as Grantham notes.

Rising prices draw in ever more investors, all convinced that prices will go on rising. Charles Kindleberger, an American economist, put it nicely: “There is nothing so disturbing to one’s well-being and judgment as to see a friend getting richer.”

The Economist, September 25, 1999

Rolf Englund 1987-10-26 För Svensk Tidskrift nr 9/1987

Kanske är det på sidan 20 i den amerikanska affärstidskriften Fortune av den 28 september 1987 man skall börja leta efter den gemensamma förklaringen till skuldkrisen, börsuppgången och börsrasen samt vad man brukar kalla stagflationen (kombinationen av inflation och arbetslöshet).

Där återfinns längst nere i hörnet, alldeles i början på det diagram som stiger mot höjderna över hela nästa sidan, som visar att den som satsade 100.000 dollar 1982 hade 395.000 dollar den 1 september 1987, ett datum.

Det datum som där angavs som utgångspunkt för uppgången på börsen var den 12 augusti 1982.

Vad var det då, frågar man sig, som hände fredagen den 13 augusti, som satte fart på världens aktiebörser? Jo, det som hände den dagen var att Mexico förklarade att man inte längre kunde betala sin utlandsskulder.

Det var skuldkrisens födelsedag.

Läs mer här

Steering monetary policy when growth is slowing and prices are accelerating is never easy.

It is particularly hard in today's unbalanced world economy, where too much depends on continued spending by American consumers who, in turn, are counting on an unsustainably frothy housing market.

At some point, America's heavily indebted consumers will need to cut back spending. And when that happens, those in the rest of the world will have to start spending more to keep the world economy growing.

The real risk is that Washington's central bankers will be too worried about stagnation and Frankfurt's too worried about inflation to allow that to happen.

The Economist print edition, May 5th 2005

The Return of STAGFLATION

Blanchard Economic Research December 30, 2000

What's more frightening inflation or recession?

The answer, of course, is both. Accelerating prices and a slow- or no-growth economy is a killer combo that's been called "stagflation" since the 1960s.

Linda Stern, The Boston Globe, April 6, 2007

Folks of a certain age might remember the stagflation which dominated the US economy in the 1970s. It was a gloomy time when energy prices (and gasoline lines) dominated the news; when whole industries slumped at the same time, and when job losses and price hikes seemed to travel in tandem.

Kudlow doomster???

Caveat Emptor

by Lawrence Kudlow

a whiff of stagflation, which is the Fed’s worst nightmare

Kudlow's Money Politic$, 23/3 2007

Is Ben's Stagflation Quagmire Gross's Real Grim Reality?

ITulip 29/3 2007

What if we get the other kind of apocalypse?

Not the bond-friendly disinflationary kind that drives interest rates down

but the bond wrecking rising inflation and contracting economy–stagflationary–type?

That's what former Harvard president Lawrence H. Summers believes.

Forecast 2007: The Goldilocks Recession

John Mauldin 5/1 2007

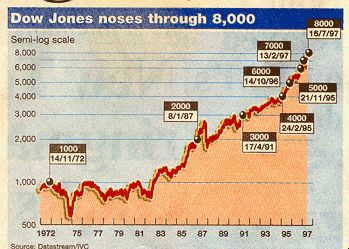

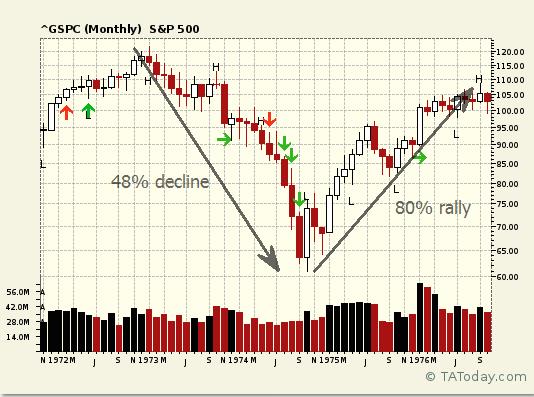

The Dow had topped out in late 1965 - early 1996, and then began an almost 30% bear market drop to the spring of 1970.

But wait, from that bottom the Dow took off. In January of 1973, the Dow topped out around 1050, or 5% above its previous high.

"On January 1, 1973, Barron's published its famous Roundtable interviews with big-name professional investors. The title was 'Not a Bear Among Them.' (By the way, the Fed Funds Rate, as of the end of December 1972, was -- 5.33%! You can't make this stuff up.)"

Of course, the Dow then proceeded to drop 40%.

Thoughts From The Frontline, Forecast 2007: The Goldilocks Recession, John Mauldin 5/1 2007

Lead us not into stagflation.

After weeks of optimism that the US economy would negotiate a soft landing and that European monetary authorities would not need to tighten their monetary policy much further, new economic data for September led to the feared equation: higher inflation plus lower industrial production equals stagflation.

All markets made the same calculation.

John Authers, Financial Times 18/10 2006 ...... full text here

One month is not enough to conclude that we are heading back to the mid-1970s.

How Edmund S. Phelps, Nobel Prize winner, got it wrong on stagflation

Those individuals who spent the new money first benefit at the expense of those who spend the new money later on

Brookes, 16/10 2006

The disastrous rise in inflation in the early 1970s was partly a result of policymakers not understanding

that the equilibrium unemployment rate had risen as productivity growth fell

Chris Giles, Economics Editor Financial Times October 9 2006

The world economy is entering a serious slowdown,

with inflation still far from under control.

Anatole Kaletsky, The Times, 4/9 2006

The most probable scenario may be that the US economy will manage a soft landing after its housing boom, in the same way as many other countries — for example Britain, Australia, Ireland, Sweden and Denmark — but there are at least two persuasive reasons to believe that America may be less lucky and sink into a serious recession.

The first is that America is so much bigger than any other economy and therefore will not be able to rely on the boost from global growth serendipitously enjoyed by these other countries just when their housing markets slowed down.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serendipity

The second is that inflation in America is now much higher than it was in Britain when the housing bubble deflated. As a result, the Federal Reserve Board will be unable to support the economy with monetary easing. Or, if it does so, inflation will accelerate even further, undermining the credibility of the Fed and the dollar and threatening America with the horrible combination of stagnation and inflation last experienced in the late 1970s.

The housing correction - and related credit crunch - appears to be at or near its low point in America

My view has been - and remains - that this episode is likely to be remembered as one of those extremes of panic or euphoria in financial markets turn out to be simply wrong.

Anatole Kaletsky, The Times July 28, 2008

The Fed has just voted for stagflation, a dreadful mix of slow-to-no growth and high inflation

Jim Jubak, CNBC 22/8 2006

The Federal Reserve seems determined to bring back the 1970s - and that won't be any Golden Oldies party for investors.

The Fed has just voted for stagflation, a dreadful mix of slow-to-no growth and high inflation that made a good part of the 1970s such a bad time for investors. According to Ibbotson Associates, the S&P 500 ($INX) showed a compounded annual return of just 3.2% from 1973 to 1979.

Mind you, those were the nominal rates of return for the period -- that's before inflation. Figure in inflation and investors lost money during these years. (For more on stagflation see my July 4, 2006, column, "Stagflation: A new peril for stocks.")

According to Keynesian economics, it should be impossible to produce inflation during a period of slow growth and high unemployment. Slow growth and high unemployment should depress demand, leading to lower prices. However, in the 1970s, despite Keynesian theory, the economy went into a nose dive and inflation soared. Real GDP actually fell in the United States from 1973 through 1975. From 1973 through 1977, real GDP grew at an annual compounded rate of just 1.3% a year. But from 1973 through 1979, inflation averaged an annual 8.8% a year.

Why did the Fed punt on inflation on Aug. 8? Because the central bank under its new chairman, Ben Bernanke, continues to believe, as it did under its previous chairman, Alan Greenspan, that it can fine tune its way to a soft landing.

Wall Street Bubbles and Crashes

Stagflation is what happens when you have little economic growth but a good bit of inflation.

It's an awful environment for stocks, and it could come back. Here's why

But until recently, I hadn't seen a convincing explanation for why this monster should rear its ugly head now. However ...

Jim Jubak, CNBC 4/7 2006

Concerns that we could see a rerun of stagflation, that dreadful mix of slow-to-no growth and high inflation that made a good part of the 1970s such a bad time for investors, have been on the rise this year. But until recently, I hadn't seen a convincing explanation for why this monster should rear its ugly head now.

However, the Bank for International Settlements, based in Basel, Switzerland, the bank for the world's central banks, warns in its most recent annual report that global stagflation is a real possibility. I find the bank's logic convincing, and I think investors need to factor the possibility of stagflation into their thinking.

Raising the spectre of stagflation BIS, the central bankers’, bank highlighted the threats that now exist after global interest rates have been "unusually low for an unusually long time"

Chris Giles, Economics Editor, Financial Times, June 26 2006

The immediate consequence for advanced economies is rising inflationary pressure now import prices are no longer falling. But the nagging longer term threat is the unwinding of the huge trade imbalances embodied in the US current account deficit and huge surpluses in China, Japan, Germany and oil exporters.

The BIS said the global imbalances could resolve themselves, but warned “it is also easy to identify forces that might make various processes of rebalancing less smooth. Some of these could imply the end will be a ‘bang’ of market turbulence, others a ‘whimper’ of slow growth for an extended period.”

The 76th Annual Report of the Bank for International Settlements for the financial year which began on 1 April 2005 and ended on 31 March 2006 was submitted to the Bank's Annual General Meeting held in Basel on 26 June 2006.

Click here

Stagflation Godzilla Returns, Attacks Finance-Based Economy!

Global Central Banks Send Anti-Inflation King Kong to Fight Back!

Will the Finance-Based Economy Survive or be Destroyed in the Great Battle?

Eric Janszen, iTulip, Inc., June 12, 2006

“The Federal Reserve raised key short-term interest rates Wednesday [today] for the first time in more than four years, launching a risky campaign to suppress inflation without stamping out economic growth,” MSNBC’s Chief economics correspondent Martin Wolk reported on June 30, 2004. A few months earlier, Bill Gross of PIMCO wrote his classic post stock market bubble reflation era analysis The Last Vigilante(PDF) about the Finance-Based Economy, from which this piece takes its name. In it he pondered what might happen when the Fed reversed direction after running short-term rates well below the rate of inflation for more than three years to keep the deflation at bay that hit a trough in 2001 following the collapse of the stock market bubble.

After the 2000 stock market crash, an economy already heavily dependent on debt became dependent on cheap credit.

This is not a U.S.-only phenomenon. As The Economist pointed out a year ago near the top of the global housing bubble in mid 2005, housing price inflation had hit 18 major economies, including South Africa, Hong Kong, Spain, France, New Zealand, Demark, China, Italy, Belgium, Ireland, Britain, Canada, Singapore and The Netherlands

Low interest rates were and are not the only fuel for inflation. The full Keynesian post-bubble reflation program included tax cuts and deficit spending that started in 2001. While the Fed has been hitting the brakes on interest rates since 2004, roll-backs of tax cuts and deficit spending intended as a short term measure to prevent the U.S. economy from falling into a Japan 1990s and U.S. 1930s style deflationary depression are nowhere to be seen. Keynes is spinning in his grave. Deficit spending, originally intended to blunt the impact of the collapsing stock market bubble, has become ideologically institutionalized by the Bush administration with the argument Deficits Don't Matter, backed with as much fabricated evidence as the administration provided to prove the existance of Weapons of Mass Destruction in Iraq.

The epic battle between Stagflation Godzilla and Anti-Inflation King Kong started to hit the markets in mid May, three months after iTulip.com re-opened after a four year hiatus to warn readers that big events were about to take place.

Back to the 1970s? Why inflation is again a spectre

Chris Giles, Financial Times 8/6 2006

Even the Bank of Japan – so long the land of falling prices – now worries more about the dangers of inflation than the “economy falling into a deflationary spiral”.

The rapid economic growth over the past four years has eliminated spare capacity in the US and Japan, reducing the scope for expansion to continue apace without boosting inflation.

There is a serious risk that high and, more important, rising energy prices will be a permanent feature of the global economy in a world characterised by surging energy demand and relatively fixed supply.

Monetary indicators, including personal borrowing, have been glowing red-hot in recent years, indicating there has been too much money sloshing around in the system even if the visible effects have been largely limited to surging asset markets, particularly property prices.

Faced with the possibility of having to explain considerably higher inflation, the last excuse cautious central bankers would want to resort to is “our models suggested prices should not have risen as they have”.

The “stagflation” (economic stagnation alongside roaring inflation)

that was common in the 1970 is now a worry once again.

The Economist 19/10 2004

Stagflation, som är en kombination av låg eller obefintlig tillväxt och snabba prisökningar, var något som världsekonomin plågades av för 25-30 år sedan. Nu används begreppet igen, när man på aktiemarknaderna målar upp hotbilder för världsekonomin.

Johan Schück, DN Ekonomi 27/5 2006

Stagflation: a term coined by economists in the 1970s to describe the previously unprecedented combination of slow economic growth and rising prices.

"Many of today's investors were still in diapers during the great stagflation of the 1970s. Those who weren't will never forget the darkest period in modern financial market history."

Stephen Roach Morgan Stanley Dean Witter

There was an economic nightmare during the 1970s that may just be coming back to cause sleepless nights for American investors: stagflation. Stagflation is the worst of both worlds: inflation and recession. It is characterized by an economy that is contracting while prices continue to rise.

Stagflation, som är en kombination av låg eller obefintlig tillväxt och snabba prisökningar, var något som världsekonomin plågades av för 25-30 år sedan.

Nu används begreppet igen, när man på aktiemarknaderna målar upp hotbilder för världsekonomin.

Johan Schück, DN Ekonomi 27/5 2006

Stagflationen på 1970-talet var en följd av den tidens kraftiga oljeprishöjningar, som sände chockvågor genom industriländernas ekonomier.

När den amerikanska ekonomin går starkt har detta en upplyftande effekt, även på den globala utvecklingen.

En svagare amerikansk tillväxt och fallande dollar får negativa följder i hela världsekonomin. Varken Europa eller Asien förmår att hålla igång en tillräckligt stark efterfrågan, utan riskerar att dras nedåt.

Även om inte faran för stagflation ska överdrivas, så har USA sina finansiella obalanser som i längden inte kan bestå. Mest uppmärksammat i omvärlden är underskottet i bytesbalansen, som har sin motsvarighet i överskott hos exempelvis Japan och Kina.

Underskottet i de offentliga finanserna, som tycks ha parkerat sig på en nivå runt fyra procent av BNP, utgör ett problem på längre sikt.

Risken är nog betydligt större när det gäller de amerikanska hushållen, som sedan något år helt har upphört att spara och i stället lånar till sin växande konsumtion

Att detta är möjligt beror på de snabbt stigande huspriserna, som får många att känna sig rikare - trots ganska blygsamma inkomstökningar. Problemet uppmärksammas särskilt av OECD i dess senaste översikt av världsekonomin.

Styrräntan ligger nu på 5,0 procent, efter att så sent för två år sedan ha varit nere på 1,0 procent. Med tiden biter en sådan åtstramning och bidrar även till att bromsa tillväxten. Ändå är det så långt till stagflation att man än så länge kan tala om mest ett hjärnspöke.

Utlösande för en kris kan vara att räntorna stiger mer än väntat, exempelvis till följd av ökad inflation. Om det då blir en nedgång i huspriserna, så betyder det att vissa hushåll hamnar på obestånd och att många andra tvingas dra ner ganska drastiskt på konsumtionen.

Sammantaget kan en sådan åtstramning få svåra följder för USA-ekonomin, där hushållens konsumtion står för cirka 70 procent av BNP. I så fall drabbas även övriga världen, som idag är starkt beroende av de amerikanska hushållens stigande efterfrågan. Resultatet riskerar att bli en global ekonomisk nedgång - kanske till och med stagflation, om oljepriset samtidigt skulle ta stora kliv uppåt.

Hotet känns dock, än så länge, inte direkt överhängande.

Men vi lever i en sårbar ekonomisk situation, vilket sent omsider har uppmärksammats av världens aktiemarknader.

Bernanke’s Sophie's Choice:

"The housing market or stock market Mr. Bernanke. You may only be able to try and save one..."

Brady Willett, May 18, 2006

Huvudfrågan kvarstår: vad händer när USA tvingas minska sitt underskott mot omvärlden, om inte överskottsländer - som Sverige - är beredda att ta ett större globalt ansvar?

Ingen centralbank, varken i USA eller någon annanstans, är villig att släppa fram en snabbt stigande inflation. Hellre låter man ekonomin gå in i en tillfällig svacka, även om den skulle övergå i recession

Johan Schück, DN Ekonomi 20/5 2006

Where is the S-word (Stagflation)?

The high debt levels actually make deflation LESS likely, not more likely, because the current monetary system - the world's greatest-ever Ponzi scheme - could not survive a bout of genuine deflation.

That is, deflation will never be a viable policy option regardless of how bad things get. Instead, the central banks of the world will likely risk destroying their currencies and obliterating the values of their bonds before they will permit deflation to occur.

Steve Saville, 6/2 2006

But assuming the central banks don't just print currency and then drop it out of helicopters, how would new currency be brought into circulation at a time when most individuals and corporations were cutting back on their borrowing/spending?

From Goldilocks to stagflation.

Real bond yields are extremely low already, suggesting that bond markets are already factoring in a significant slowdown in economic growth. However, bond markets are not yet priced for a significant pick-up in consumer price inflation.

Joachim Fels, Morgan Stanley, 14/9 2005

"Risk för global kris"

Morgan Stanleys chefsekonom varnar för sammanbrott i världsekonomin

DN 9/9 2004 Reporter Johan Schück

Deflation is in the Cards. Yes Readers, that is correct.

The answer to the "Great Flation Question" is DEFLATION.

I am not going to wimp out and say "stagflation"

and rest assured it is not "inflation" which means that the "hyper-inflation" that many see coming is totally laughable.

Michael Shedlock 25/4 2005